Church of Romania

| Patriarchate of Romania | |

| Founder(s) | Apostle Andrew |

| Autocephaly/Autonomy declared | 1865 |

| Autocephaly/Autonomy recognized | 1885 by Constantinople |

| Current primate | Patr. Daniel |

| Headquarters | Bucharest, Romania |

| Primary territory | Romania, Moldova |

| Possessions abroad | United States, Canada, Western Europe |

| Liturgical language(s) | Romanian |

| Musical tradition | Byzantine Chant, Choral |

| Calendar | Revised Julian, Julian (in Moldova) |

| Population estimate | 18,817,975 [1] |

| Official website | Church of Romania |

The Church of Romania is one of the autocephalous Orthodox churches. The majority of Romanians in Romania by a very wide margin (about 20 million, or 86.7% of the population, according to the 2002 census data) belong to it. In terms of population, the Church of Romania is second in size only to the Church of Russia.

In the Romanian language it is most often known as Ortodoxie, but is also sometimes known as Dreapta credinţă ("right/correct belief"—compare to Greek ορθοδοξια, "straight/correct belief"). Orthodox believers are also known as ortodocşi, dreptcredincioşi or dreptmăritori creştini.

The primate is His Beatitude Daniel (Ciobotea), Archbishop of Bucharest, Metropolitan of Ungro-Vlachia, and Patriarch of All Romania, Locum Tenens of Caesarea in Cappadocia.

Contents

[hide]History

Some Romanian Orthodox regard their church to be the first national, first attested, and first apostolic church in Europe and view the Apostle Andrew as the church's founder.

Most historians, however, hold that Christianity was brought to Romania by the occupying Romans. The Roman province had traces of all imperial religions, including Mithraism, but Christianity, a religio illicita, existed among some of the Romans.

The Roman Empire soon found it was too costly to maintain a permanent garrison north of the lower Danube. As a whole, from 106 AD a permanent military and administrative Roman presence was registered only until 276 AD. (In comparison, Britain was militarily occupied by Romans for more than six centuries—and English is certainly not a Romance language, while the Church of England had no Archbishop before the times of Pope St. Gregory the Great.) Clearly, Dacians must have been favored linguistically and religiously by some unique ethnological features, so that after only 169 years of an anemic military occupation they emerged as a major Romance people, strongly represented religiously at the first Ecumenical Councils, as the Ante-Nicene Fathers duly recorded.

When the Romanians formed as a people, it is quite clear that they already had the Christian faith, as proved by tradition, as well as by some interesting archeological and linguistic evidence. Basic terms of Christianity are of Latin origin: such as church (biserică from basilica), God (Dumnezeu from Domine Deus), Pascha (Paşti from Paschae), Pagan (Păgân from Paganus), Angel (Înger from Angelus). Some of them (especially Biserică) are unique to Orthodoxy as it is found in Romania.

Very few traces can be found in the Romanian names that are left from the Roman Christianity after the Slavic influence began. All the names of the saints were preserved in Latin form (the following are archaic versions of the words): Sântămăria (today Sfânta Maria, the Theotokos), Sâmpietru or Sâmpetru (today Sfântul Petru, Apostle Peter), Sângiordz or Sângeorz (today Sfântul George or Sfântul Gheorghe, St. George) and Sânmedru (today Sfântul Dumitru, St. Demetrius). The non-religious onomastic proof of pre-Christian habits, like Sânziana and Cosânzeana (from Sancta Diana and Qua Sancta Diana) is only of anecdotal value in this context. Yet, the highly spiritualized places in the mountains, the processions, the calendars, and even the physical locations of the early churches were clearly the same as those of the Dacians. Even the Apostle Andrew is known locally as the Apostle "of the wolves"—with very old and large connotations, whereby the wolf's head was an ethnicon and a symbol of military and spiritual "fire" for Dacians.

Christianity in Scythia Minor

While Dacia was only for a short time part of the Roman Empire, Scythia Minor (modern Dobrogea) was part of it much longer and after the breakdown of the Roman Empire, it became part of the Byzantine Empire.

The first encounter of Christianity in Scythia Minor was when St. Andrew, brother of St. Peter, and their disciples passed through it in the first century. Later on, Christianity became the predominant faith of the region, proven by the large number of remains of early Christian churches. The Roman administration was ruthless with the Christians, proven by the great number of martyrs.

Bishop Ephrem, killed in on March 7, 304, in Tomis, was the first Christian martyr of this region and was followed by countless others, especially during the repression ordered by emperors Diocletian, Galerius, Licinius and Julian the Apostate.

An important, impressive number of dioceses and martyrs are first attested during the times of Ante-Nicene Fathers. The first known Daco-Roman Christian priest Montanus and his wife Maxima were drowned, as martyrs, because of their faith, on March 26, 304.

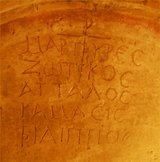

The 1971 archeological digs under the paleo-Christian basilica in Niculiţel (near ancient Noviodunum in Scythia Minor) unearthed an even older martyrion. Besides Zoticos, Attalos, Kamasis, and Filippos who suffered martyrdom under Diocletian (304-305), from under the crypt were unnearthed the relics of two previous martyrs who died during the repressions of Emperor Decius (249-251].

The names of these martyrs had been placed since their death in church records, and the find of the tomb with the names written inside was astonishing. The fact that the relics of the famous St. Sava the Goth (martyred by drowning in the river Buzău, under Athanaric on April 12, 372) were reverently received by St. Basil the Great conclusively demonstrates that (unlike bishop Wulfila), St. Sava was a follower of the Nicene faith, not a heresiarch like Arius.

Once the Dacian-born Emperor Galerius proclaimed freedom for Christians all over the Roman Empire in 311, the city of Tomis alone (modern Constanţa) became a metropolis with as many as 14 bishoprics.

Middle Ages

Following the complex relationship of the Byzantine Patriarchates and Bulgarian kingdoms, Romanians adopted Church Slavonic in the liturgy from the early 9th century. However, most of the religious texts were learned by heart by priests who either did not understand Slavic languages or always wanted to be understood by their own community, or both. Some priests used to mumble (a boscorodi) the sermon, using certain Slavic prefixes, so at least it would sound like Slavonic.

Since Dacia south of the Danube was also known as Vlahia Mare ("Greater Wallachia"), the region north of the Danube was known as Ungro-Vlahia—"Hungary-Wallachia." This important geographical and ethnogenetic fact of Romania is still reflected into the name of the first Metropolis of Ungro-Vlachia, which was founded in 1359 in Curtea de Argeş. Another Romanian Metropolis was founded in 1401 in Suceava, Moldova.

Translation of the Bible

Ecclesiastical life flourished in all organized forms on both sides of the Lower Danube. However, metropolia for the Romanians north of the Danube were only created in the late 13th century and early 14th century, according to the political developments there. Many religious texts were to be periodically transcribed until the 16th century in Church Slavonic only.

However, important Romanian language translations certainly circulated, including the Codicele Voroneţean (the Codex of Voroneţ). The Bucharest Bible (Biblia de la Bucureşti) was the first complete Romanian translation of the Bible in the late 17th century. It was published in 1688 during the reign of Şerban Cantacuzino in Wallachia and is considered a mature and highly developed work.

Its cultural import is not unlike that of the King James Version for the English language. This could not have been achieved without much previous (and perhaps as yet unknown) anonymous translation work. For this, a wealth of Byzantine manuscripts, brought north of the Danube in the "Byzance after Byzance" movement described by famous historian Nicolae Iorga is an outstanding proof.

After this time, the importance of Church Slavonic and Greek in the Church of Romania began to fade. 1736 was the year when the last Slavonic liturgy was published in Wallachia, but only in 1863 did Romanian become officially the only language of the Romanian church.

Although most of the time under foreign suzerainty (under the Ottoman Turks in Moldova and Wallachia and under Hungarian rule in Transylvania), Romanians characteristically kept their Orthodox faith as part of their national identity.

The Uniate Church

In 1698 in Transylvania, a small number of Romania's Orthodox Christians granted ecclesiastical authority to the Pope of Rome, but retained the Orthodox rite. Thus, they went into schism from the Orthodox Church.

This action is seen by some historians as a political move designed to obtain the equality of rights with Roman Catholic citizens. Indeed, by becoming members of the "Greek-rite Roman Catholic" church, a minority of Romanians in Transylvania eventually managed to be recognized as a nation by the Hapsburg rulers, achieving status equal to the three Transylvanian peoples collectively known as the Unio Trium Nationum. Along with this came the arrival of the Jesuits who attempted to align Transylvania more closely with Western Europe.

This ecclesiastical group is known today as the Romanian Greek-Catholic Uniate Church.

Recent history

The Romanian Orthodox Church has been fully autocephalous since 1885. Many Romanians believe the Orthodox faith to be an essential part of their national and ethnic identity, although a minority of Romanians are members of other faiths.

The Church in Moldova

Romanians in the Republic of Moldova (a region formerly known as "Moldavia") belonging to the Metropolis of Bessarabia, having resisted Russification for 192 years (after the annexation of Bessarabia by the Russian Empire in 1812), are improbably said to currently number about 2 million. The Metropolis of Bessarabia is part of the Romanian patriarchate. In 2001 at the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights, the Metropolis won a landmark legal victory against the government of the Republic of Moldova for its official recognition in that country.

Following the creation of Greater Romania after the First World War, Orthodox Christians in Moldova became part of the Church of Romania. Following Stalin's annexation of the country in 1944, the church there was again brought under the authority of the Church of Russia. Following the fall of communism, Moldova's government refused to allow the Romanian church to exercise any authority in Moldova. The Bessarabian metropolis was created by the Romanian Patriarchate to cater for those clergy and people wanting to return part of Moldova to Romanian rule. With the European Court ruling of 2001, the Metropolis of Bessarabia was declared to be a part of the Church of Romania and permitted to operate in Moldova.

2003 figures show the Metropolis of Bessarabia has 84 parishes in Moldova while the autonomous Moldovan Orthodox Church has 1080 parishes. [2]

Unique features

The Romanian Orthodox Church is one of only three autocephalous or autonomous Orthodox churches using a Romance language as a principal liturgical language. The autocephalous Church of Russia also uses Romanian as a principal liturgical language in its autonomous Moldovan Orthodox Church. The autonomous Metropolis of Bessarabia also uses Romanian as its principal language. Various jurisdictions of the Orthodox Church in France and other European countries also use different romance languages as their principal liturgical language.

Byzantine religious records also mention a unique form of bishopric in the region—namely the chorepiscopate or countryside episcopacy—as contrasted with the better-known religious centers in large cities. This office can be compared to the abbot-bishops of Ireland, who united the functions of countryside abbot with that of diocesan bishop in another country that did not emphasize an urban episcopate, at least for a time.

The very word church in Romanian, biserică, is unique in Europe. It comes from Latin basilica (from the Greek βασιλικα, meaning "communications received from the king" and "the place where the Emperor administered justice"), rather than ecclesia (from εκκλησία, meaning "those called out").

Canonical status

The Church of Romania is organized as a patriarchate. The highest hierarchical and canonical authority of the church is the Holy Synod.

Organization

There are six metropolia and ten archdioceses in Romania, containing 14,035priests and deacons. Almost 631 monasteries exist inside the country for some 8,059 monks and nuns. Three diasporan metropolia and two diasporan dioceses function outside Romania proper.

As of 2004, there are, inside Romania, fifteen theological universities where more than 10,898 students (some of them from Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Serbia) currently study for a doctoral degree. More than 15,116 churches exist in Romania for the Orthodox faithful. As of 2002, almost 1000 of these were either in the process of being built or rebuilt. [[3]]

Famous theologians

Father Dumitru Stăniloae (1903-1993) was one of the greatest Orthodox theologians of the 20th century. His magnum opus, aside from his Duhovnicesc ("deepest spiritual"), is the comprehensive collection, compiled over 45 years, known as the Romanian Philokalia.

List of Patriarchs

- Miron (1925-1939)

- Nicodim (1939-1948)

- Iustinian (1948-1977)

- Iustin (1977-1986)

- Teoctist (1986-2007)

- Daniel (2007-)

Structure of the Patriarchate

Metropolitan See of Muntenia and Dobrogea

- Archdiocese of Bucharest

- Archdiocese of Tomis

- Archdiocese of Târgovişte

- Diocese of Buzău

- Diocese of Argeş and Muscel

- Diocese of Dunărea de Jos

- Diocese of Slobozia and Călăraşi

- Diocese of Alexandria and Teleorman

- Diocese of Giurgiu

Metropolitan See of Moldova and Bucovina

- Archdiocese of Iaşi

- Archdiocese of Suceava and Rădăuţi

- Diocese of Roman

- Diocese of Huşi

Metropolitan See of Transylvania (Ardeal)

- Archdiocese of Sibiu

- Diocese of Covasna and Harghita

Metropolitan See of Cluj, Alba, Crişana and Maramureş

- Archdiocese of Vad, Feleac, and Cluj

- Archdiocese of Alba Iulia

- Diocese of Oradea (including Bihor and Sălaj)

- Diocese of Maramureş and Sătmar

Metropolitan See of Oltenia

- Archdiocese of Craiova

- Diocese of Râmnic

- Diocese of Severin and Strehaia

Metropolitan See of Banat

- Archdiocese of Timişoara

- Diocese of Arad, Ienopole, and Hălmagiu

- Diocese of Caransebeş

- Romanian Orthodox Diocese in Hungary (Guila)

Autonomous Metropolitan See of Bessarabia

Romanian Orthodox Metropolitan See for Germany and Central Europe

Romanian Orthodox Metropolitan See for Western and Southern Europe

Romanian Orthodox Archdiocese in America and Canada

Romanian Orthodox Diocese of Dacia Felix (Serbia)

Romanian Orthodox Diocese of Australia and New Zealand

Romanian Saints

- Daniel the Hermit

- Evangelicus of Tomis

- Gherman of Dobrogea

- John Cassian

- John the New of Suceava

- Sansala

- Sava the Goth

- Stephen the Great

- List of Romanian Saints

Churches and Monasteries

| Autocephalous and Autonomous Churches of Orthodoxy |

| Autocephalous Churches |

| Four Ancient Patriarchates: Constantinople · Alexandria · Antioch · Jerusalem Russia · Serbia · Romania · Bulgaria · Georgia · Cyprus · Greece · Poland · Albania · Czech Lands and Slovakia · OCA* · Ukraine* |

| Autonomous Churches |

| Sinai · Finland · Estonia* · Japan* · China* · Ukraine* |

| The * designates a church whose autocephaly or autonomy is not universally recognized. |

Source

- Wikipedia:Romanian Orthodox Church (as of Jan. 22, 2005) provided the initial form, but article has been significantly revised and expanded in the interim.

External links

- The Romanian Patriarchate (official site)

- Biserica Ortodoxa Romana (in Romanian and English)

- Portal Ortodox Romanesc (in Romanian)

- On Science and Faith: Romanian Orthodox Reflections (in Romanian, French, and English)

- OrthoLogia: Jurnal de apologetica Ortodoxa

- Eastern Christian Churches: The Orthodox Church of Romania by Ronald Roberson, a Roman Catholic priest and scholar

- "Romanian Orthodox Church" at Wikipedia

Churches and Monasteries

History

- The Role played by the Christianity in the Genesis of the Romanian People

- Romanian Orthodox Church - History

Romanian Orthodoxy outside Romania

- Mitropolia Ortodoxă Română a Europei Occidentale şi Meridionale Romanian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Western and Southern Europe (in French, Spanish, and Romanian)

- Mitropolia Ortodoxă Română pentru Germania şi Europa Centrală: Romanian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Germany and Central Europe (in German and Romanian)

- Romanian Church of Paris (in Romanian and French)

- Romanian Orthodox Church in London (in Romanian and English)

- Romanian Orthodox Archdiocese in America and Canada (Church of Romania; in Romanian and English)

- Romanian Orthodox Episcopate of America (OCA)

- MOLDOVA: Government Fails in Bessarabian Church Appeal

- Metropolitan Church of Bessarabia and Others v. Moldova