Resurrection

Contents

Resurrection of Christ

The Gospels narrate that after Christ's Passion and suffering on the Cross, he was laid in a tomb which was donated by Joseph of Arimathea. After three days in the tomb, Christ had descended into Hades and broke the bonds of Death through his resurrection. The belief of Christ's Holy Resurrection is reiterated in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed.

This Resurrection, commemorated every year on Great and Holy Pascha and every week on the Lord's Day, is the most fundamental belief of the Church. It confirms the authenticity of Christ's teachings, His Godhood and Manhood, and proves the veracity of His work in redeeming mankind from the Fall. Conquering sin and its result, death, Christ is often referred to as the "New Adam," bestowing new life to humanity. As the Apostle Paul states, "For as by a man came death, by a man came also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive."[1]

The Resurrection of Christ is foretold in several Books of the Old Testament, as in The Book of Hosea, where the prophet says, "After two days He shall revive us: in the third day He will raise us up, and we shall live in His sight."[2]

Death Before the Ressurection of Christ

Before the ressurection, all the dead would go to Sheol (Hades) wether they were righteous or not. It was a place of darkeness and death.. After Christ was laid into the tomb, he descended into Hades and broke the bonds of death and let out all of the people therein, such as King David and Solomon, John the Baptist, Adam and Eve among others.

Resurrection of the dead

During Jesus' time, there was much debate amongst the Jews over the Resurrection of the dead. One such faction, the Pharisees, preached the resurrection, while the Sadducees, rejecting it, believed in no afterlife whatsoever.

The Church teaches that Christ's Resurrection guarantees our salvation and that together with His Ascension it brings to fruition God's union with us for all eternity. While the Resurrection has not yet abolished the reality of death, it has revealed its powerlessness over us in Christ.[3]

Since mankind shares in Christ's Resurrection, the Church teaches that all mankind shall rise from the dead at the Final Judgment. Therefore, Christ is the "first fruits of those fallen asleep."[4] In the Acts of the Apostles, St. Paul confirms this by saying, "...he hath appointed a day, in the which he will judge the world..."[5] and "...there shall be a resurrection of the dead, both of the just and unjust..."[6] While the Church does not go into much detail as to the exact events of the Last Day, it is believed that those who love the Lord and follow His commandments will find paradise in His presence, while those who hate him will find infinite torture.

Iconography

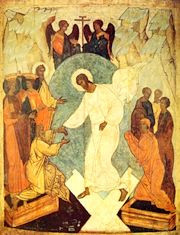

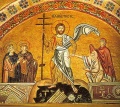

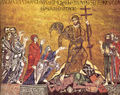

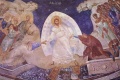

In iconography, according to the Byzantine iconographic type, the Resurrection — as early as the eighth century — is portrayed primarily by the Descent of the Saviour into Hades. Our Lord is depicted pulling up Adam and Eve out of their sepulchers while trampling upon the gates of Hades (death). In the background stand the Old Testament patriarchs, prophets, and other figures, including John the Forerunner, who announced Jesus' advent.

- “This iconographic type represents the Lord in Hades surrounded by a radiant glory; He is trampling upon the demolished gates of Hell and bears in His left hand the Cross of the Resurrection, while with His right hand He raises from a sarcophagus Adam, who represents the human race.”[7]

It is very striking that St. John of Damascus (676-749) knows of an Icon of the Resurrection, which he considers consonant in every respect with the ecclesiastical tradition up to his time, and which he describes:

- “We have received Her [the Holy Church of God] from the Holy Fathers thus adorned, as the Divine Scriptures also teach us: to wit, with the Incarnate OEconomy of Christ,... the Annunciation of Gabriel to the Virgin, etc., the Nativity, etc....; and likewise, the Crucifixion, etc... ; the Resurrection, which is the joy of the world—how Christ tramples on Hades and raises up Adam.”[8]

One authoritative contemporary theologian, Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos) of Nafpaktos states that:

- “The Church decided to regard the Descent into Hades as a true Icon of the Resurrection.... The quintessential Icon of the Resurrection of Christ is considered to be His Descent into Hades... To be sure, there are also Icons of the Resurrection which depict Christ’s appearance to the Myrrh-bearing women and the Disciples, but the Icon of the Resurrection par excellence is the shattering of death, which took place at the Descent of Christ into Hades, when His soul, together with His Divinity, went down into Hades and freed the souls of the Righteous ones of the Old Testament, who were awaiting Him as their Redeemer.”[9]

By contrast, the Latin-style iconographic depiction of the Resurrection differs significantly. This type was created in the eleventh century in the West and became familiar through Giotto (Giotto di Bondone, 1266-1337), although its different forms, especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, vary quite widely:

- “The Lord is represented holding a banner of victory as He is raised in the air as if by a vigorous jump from a sarcophagus tomb, whose slate covering is raised by an angel, obviously to permit Him to exit, while the guards are shown fallen upon the ground’; ‘[T]he Western type showing Christ jumping out of the grave was imposed upon Orthodox iconography during the Turkish domination (especially from the 17th century) through the influence of the West. It became practically the prevalent Icon of the Resurrection, when in essence it is a type not only untraditional but unorthodox.”[10]

Orthodox theology regards the Latin/Western type, vis-à-vis the representation of the Resurrection, “as unhistorical, simply impressionistic, and essentially unorthodox,” and characterizes its adoption as “a compromise to the detriment of the Orthodox Tradition of worship and doctrine,” which “[is] in no way permissible,” since it leads “to artistic syncretism.”[11]

The Orthodox Icon of the Resurrection is a dogmatic Icon, that is, it expresses a dogmatic truth, the real meaning of the event and, as such, transcends the historical place and the temporal moment at which it occurred. “The quality of theological tradition is reflected in the Icon of the Resurrection, which requires a purely mystical interpretation of this event.”[12] This dogmatic Icon of the Resurrection highlights, with truly exceptional emphasis, not an individual historical event (the bodily Resurrection of the Saviour), nor an historical moment (the Saviour’s egress from the Tomb), but, rather, the dogma of the abolition of Hades and death as well as the Resurrection of humanity. “The Resurrection of Christ is simultaneously also the Resurrection of humanity; the Resurrection is not only the Resurrection of Christ,” but a majestic universal event, a “cosmic event”;[13] “Christ does not come out of the tomb but out from ‘among the dead,’ ek nekron, ‘coming up out of devastated Hades as from a nuptial palace.’”[14]

The Resurrection, according to the Western type, “portrays a historical moment,” that is, it essentially “starts from Christ’s egress from the tomb,”[15] Whereas according to the Orthodox type, “it reveals, that is, makes manifest the victory of the Cross; the Descent into Hades is already a Resurrection; the great triduum mortis constitutes the mystical days in which the Resurrection is accomplished.”[16]

The Holy Resurrection of Our Savior, as a mystery, was invisible and outside the laws and processes of other resurrections, since through the Resurrection and in the Resurrection we do not have a simple resuscitation of the Master’s Body and its egress from the sepulchre, as, for example, in the case of St. Lazarus (a miracle perceptible to all, and the [eventual] return of his body to corruption), but its transition, as being henceforth “one with God” [ὁμόθεος] and, in an ineffable mystery, to uncreated reality; that is, we have an ontological transformation. A lucid commentary on this Patristic viewpoint is provided by Leonid Ouspensky, who writes:

- “The unfathomable character of this event for the human mind, and the consequent impossibility of depicting it, is the reason for the absence, in traditional Orthodox iconography, [of any depiction] of the actual moment of the Resurrection.”[17]

The so-called Byzantine type then, as the authentically Orthodox dogmatic Icon of the Resurrection renders perceptible the Resurrectional Apolytikion:

- "Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life."

Gallery

Descent Into Hades / Harrowing of Hell

Anastasis, Nea Moni of Chios, Greece, 11th c.

The Anastasis fresco in the parekklesion of the Chora Church, Istanbul, 14th c.

Five part Resurrection icon, Solovetsky Monastery

17th c.

Myrrh-Bearing Women / Angel at the Tomb

The earliest crucifixion in an illuminated manuscript, also shows the resurrection.

Rabbula Gospels, 6th c.

See Also

References

- ↑ I Corinthians 15:21-22.

- ↑ Hosea 6:2.

- ↑ Hebrews 2:14-15.

- ↑ I Corinthians 15:20.

- ↑ Acts 17:31.

- ↑ Acts 24:15.

- ↑ Constantine D. Kalokyris. The Essence of Orthodox Iconography. Transl. Peter A. Chamberas. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross School of Theology, 1971. pp. 33.

- ↑ St. John of Damascus. “Demonstrative Discourse Concerning the Holy and Precious Icons.” §3, Patrologia Græca, Vol. XCV, cols. 313D-316A.

- ↑ Metropolitan Hierotheos of Naupaktos. Οἱ Δεσποτικὲς Ἑορτές [The feasts of the Lord]. Lebadeia, Greece: Hiera Mone Genethliou tes Theotokou [Pelagias], 1995. pp.262,263.

- ↑ Kalokyris. The Essence of Orthodox Iconography. pp.33,35.

- ↑ Kalokyris. The Essence of Orthodox Iconography. p.36.

- ↑ Michel Quenot. Ἡ Ἀνάσταση καὶ ἡ Εἰκόνα [The Resurrection and the Icon]. Katerine: Ekdoseis “Tertios,” 1998. p.94.

- ↑ Branos. Θεωρία Ἁγιογραφίας. pp.216,217.

- ↑ Paul Evdokimov. The Art of the Icon: A Theology of Beauty. Transl. Fr. Steven Bigham. Redondo Beach, CA: Oakwood Publications, 1990. p.325.

- ↑ Branos. Θεωρία Ἁγιογραφίας. pp.225.

- ↑ Protopresbyter Georges Florovsky. “Ὁ Σταυρικὸς Θάνατος” [Of the death on the Cross]. In: Ἀνατομία Προβλημάτων τῆς Πίστεως [An analysis of matters of faith]. Transl. Archim. Meletios Kalamaras. Thessalonica: Ekdoseis Bas. Regopoulou, 1977. pp.79-81.

- ↑ Leonid Ouspensky, in Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky. The Meaning of Icons. Transl. G.E.H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovsky. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1982. pp.187,185.

Sources

- Chancery of the Holy Synod in Resistance. REPORT: The Holy Icon of the Resurrection, Basic Principles for Overcoming an Unfruitful Dispute. St. John the Theologian, September 26, 2007 (Old Style).

- Abp. Hilarion (Alfeyev). Christ the Conqueror of Hell: The Descent into Hades from an Orthodox Perspective. St Vladimirs Seminary Press, 2009. 232pp. ISBN 9780881410617