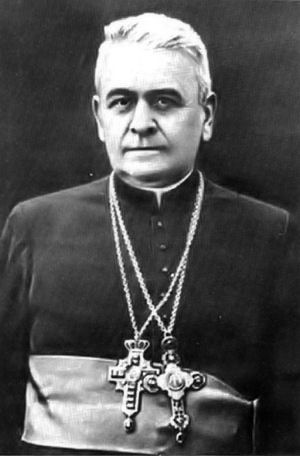

Gabriel Kostelnik

The New Hieromartyr[note 1] Protopresbyter Dr. Gabriel Kostelnik, also Havryil Kostelnyk, Havriil Kostelnik or Gabriel of Galicia ((Russian)

Костельник, Гавриил Фёдорович, (Serbian) Хавријил Костељник, June 15, 1886 - September 20, 1948) was a Carpatho-Russian priest who returned to the Orthodox Church soon after the end of World War II. He was an outstanding church leader, theologian, philosopher, religious publicist, poet, playwright and prose-writer.[1] Controversially however, in March 1946 he presided over the state-sponsored Reunion Council in Lvov (Lvov Assembly / Lviv Sobor) calling for the return of all Uniates to the Orthodox Faith, before he was assassinated during the political and religious turmoil of the late 1940s.

Contents

Life

Gabriel Kostelnik was born on June 15, 1886 in Ruski Kerestur, now Serbia, into the Uniate Church. His father Fedor and mother Anna Kakai had six children. Besides Gabriel, there were two brothers, Michael and Janko, and three sisters, Maria, Jula, and Helena. Gabriel 's father was a member of the village government from 1895 to 1919.

He attended the local primary school of his village for the first six years of his education from 1894 to 1898. His next four years in grammar school was split, two years in Vinkovci, Croatia and two years in Zagreba, Croatia. In 1906, he enrolled in the theological faculty of the University of Zagreb. After his first year, the dean of the Faculty sent him to the Lvov Theological Seminary from which he graduated in 1911. At that time he became a member of the archdiocese of Lvov and received a scholarship for postgraduate studies.

He continued these studies at Freiburg University in Switzerland, receiving in 1913 a doctorate in philosophy. In 1915, he also received a doctorate from the University of Lvov. While an excellent academic theologian and Church historian, his interests also included poetry and philosophy. He was fluent in his local language as well as Ukrainian, Croatian, German, Polish, and Latin.

In 1913, he married the daughter of the principal of the Lvov Ruska gymnasium, Eleonora Zaricka. The couple had five children: Sviatoslava, Irene, Bohdan, Zenon, and Christina.

Also in 1913, Gabriel was ordained a priest in the Uniate Church in Lvov. After his ordination he served in the Cathedral of the Transfiguration in Lvov. He also became a professor of theology and philosophy at the Greek Catholic Theological Seminary in Lvov (1920–8) and the Greek Catholic Theological Academy (1928–30). He also edited the religious journal Nyva (1922–32).[2]

In the late 1920s Gabriel emerged as a critic of the Vatican's Uniate policy and became the leading representative of the ‘Eastern’ (anti-Latinization) orientation among the Greek Catholic clergy.[2]

His continuing studies of the Church Fathers convinced him of the correctness of the position of the Orthodox Church. In 1930, after expressing his views in published papers, Fr. Gabriel was dismissed from his position with the academy. Not cowered by his dismissal, Fr. Gabriel continued his critique of Catholicism throughout the 1930s. At the Uniate congress in 1936 in Lvov, Father Gabriel read a paper on the Ideology of the Unia, arguing that the Greek Catholic Church was doomed and that it was necessary to return to the fathers’ faith.[1] He courageously developed the same theme at the Lvov diocesan clergy congress in 1943.[1] He was convinced of the error of the Unia and its wrongful effect on church life. During this time he formed a body of supporters who agreed with his position.

Lvov Assembly (1946)

In the midst of the chaos at the end of World War II, Fr. Gabriel and his supporters called for a return to the Mother Orthodox Church. As the pre-war political alignments collapsed around them, Patriarch Alexei I of Moscow welcomed their desire for the return of the Uniate clergy and faithful to Orthodoxy.[note 2]

On February 23, 1946, Metr. John of Kiev received Fr. Gabriel and twelve other priests from the Unia to Orthodoxy. By the end of the month two of these priests, Antoni Pelvetsky and Mykhailo Melnyk, had been consecrated bishops. Over the following months additional priests and laypeople joined Fr. Gabriel's movement.

Orthodox scholar Dr. Vladimir Moss has written the following historical-critical account of the council:

"After the Soviet victory in the war, it was the turn of the Soviets and the Sovietized Moscow Patriarchate to apply pressure. Towards the end of the war it was suggested to the uniate episcopate in Western Ukraine that it simply “liquidate itself”. When all five uniate bishops refused, in April, 1945, they were arrested. Within a month a clearly Soviet-inspired “initiative movement” for unification with the MP headed by Protopresbyter G. Kostelnikov appeared. By the spring of 1946 997 out of 1270 uniate priests [78%] in Western Ukraine had joined this movement. On March 8-10 a uniate council of clergy and laity meeting in Lvov [in St George's Cathedral] voted to join the Orthodox Church and annul the Brest unia with the Roman Catholic Church of 1596. Those uniates who rejected the council were forced underground. Similar liquidations of the uniate churches took place in Czechoslovakia and Romania… Central Committee documents show that the whole procedure was controlled by the first secretary of the Ukrainian party, Nikita Khruschev, who in all significant details sought the sanction of Stalin."[3]

The Uniat clergy that renounced the Latin errors were united with the Orthodox Church through the sacrament of Confession by the newly-received ex-Uniat clergy, followed by the concelebration of the Divine Liturgy, and a message was sent to Patriarch Alexei I (Simansky) of Moscow, which welcomed the day that spiritual freedom had arrived.[4]

Byzantine-Ruthenian Catholic priest Christopher Lawrence Zugger argues that Father Gabriel was motivated partly from the hope of saving his son (who, he had been told was a prisoner of the Soviets), partly out of anti-Latin Catholic feelings, and partly out of conviction.[5] The Encyclopedia of Ukraine adds that Fr. Gabriel's theological position made him a target of NKVD pressure and blackmail during the 1939–41 Soviet occupation of Galicia, when the authorities first tried unsuccessfully to have him organize an ‘away from Rome’ schism in the Ukrainian Catholic church; and when the Soviets reoccupied Galicia in 1944 and arrested the entire Ukrainian Catholic episcopate, he was finally compelled to assume chairmanship of the Initiating Committee for the Reunification of the Greek Catholic Church with the Russian Orthodox Church.[2]

In sum, the religious movement which started with the anti-Latinization orientation among the Greek Catholic clergy led by Fr. Gabriel, and which culminated in the state-sponsored Synod of Lvov, occured at the same time that the political atmosphere in the area changed, as the remnants of the Nazi regimes, various nationalistic groups, the Bolshevik forces, and religious differences all collided with the sincerity of the people. In that environment, many of the clergy and laypeople returning to Orthodoxy became victims of fanatics, both religious and political.

Death

In July 1948, Fr. Gabriel took an active part in the celebrations in Moscow on the occasion of 500th anniversary of the autocephaly of the Russian Orthodox Church.[6]

On September 20, 1948, after the Divine Liturgy Fr. Gabriel was attacked on the steps of the Cathedral of the Transfiguration in Lvov and killed by one, Vasily Pankiv, a terrorist who killed himself immediately after his deadly assault.

According to the official Soviet version, Pankiv was a member of the terrorist group led by Roman Shukhevich, chief of the Ukrainian Rebel Army (UPA).[6][7] In addition, an official bulletin printed in the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate (1948, № 10) and signed by Metropolitan Nicholas (Yarushevich) stated that Kostelnik was "killed by an agent of the Vatican."[8]

However, representatives of the UPA denied any involvement in the murder. And the Encyclopedia of Ukraine states that although "Soviet authorities have blamed his murder on the Vatican and Ukrainian nationalists, the evidence suggests that the assassination was masterminded by the Soviet police."[2]

Fr. Gabriel was buried in the Lychakov cemetery in Lvov. His funeral was attended, at least according to some Soviet authors, by around 40,000 people. Church leaders decided to inform the highest Soviet administrators of the 'great loss' they suffered. Among others, J.V. Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev were contacted.[9]

Commemoration

On September 20, 1998, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the demise of Protopresbyter Gabriel Kostelnik, the Divine Liturgy was celebrated in St. George’s church, followed by a Panikhida at the tomb of Father Gabriel at the Lychakov cemetery conducted by Archbishop Augustine (Markevitch) of Lviv and Drogobych.

Later, a historic conference was held on the theme ‘Protopresbyter Gabriel Kostelnik and His Role in the Revival of Orthodoxy in Galicia’.[1][note 3] A message from His Holiness Patriarch Alexei II said that "the death of Protopresbyter Gabriel Kostelnik was an irretrievable loss for the spiritual life of his legacy – the people of God who reunited with Holy Orthodoxy at the Church Council of Lvov and for the Russian Orthodox Church as a whole."[1]

On September 19-20, 2008, the Lviv Diocese of the Ukraine Orthodox Church celebrated the 60th anniversary of the death of Father Gabriel.

Glorification

Fr. Gabriel has been under consideration for glorification. According to Archbishop Augustine (Markevitch) of Lviv and Galicia, the Church has already begun to work on the appropriate documents.[6][note 4]

Works

Father Gabriel's early poetry and prose were written in his native dialect, and he is considered the creator of the Bačka literary language.[2]

- Idyllic Sequence - From My Village, 1904.

- Dissertation: De Principiis Cognitionis Fundamentalibus (About the Basic Principles of Cognition), Leopoli, 1913.

- Arise Ukraine, a poem in Ukrainian, 1918.

- Boundaries of Democracy, Lvov, 1919.

- Song for God, a poem of fifty eight homilies, 1922.

- Grammar of Bach-Rusyn language, 1923.

- Jephthah's Daughter, a play, 1924.

- Dew Drops and the Sun, contains thirty one lyrical essays, 1931.

- Christian Apologetics, where he considers reality and correctness of Christianity; the book consists of seven chapters including: 1.Religion 2.God 3.Genesis 4.Soul 5.Epiphany 6.The Church of Christ 7.Causes of atheism.

Notes

- ↑ Fr. Gabriel has not yet been glorified, although he is currently under consideration for canonization by the Church of Ukraine. In this regard, it has been suggested that the title "Passion-bearer" should be considered as a more accurate title for him based on the events of his life.

- ↑ It is important to note that there were precedents in the history of the Uniate church similar to Father Gabriel's movement. According to Patriarch Alexei II (Ridiger) of Moscow, the Union of Brest, enforced in 1596, retained a strong internal opposition throughout its 400 years which would resolutely break away in favorable times, citing three outstanding examples:

- "Greek Catholics in Belorussia, Lithuania, Volhynia and Podolia, led by the Uniate bishop Joseph (Semashko) and his colleagues representing the high-ranking Greek Catholic clergy, reunited with the Russian Orthodox Church in 1839 (Synod of Polotsk).

- The same was done by Greek Catholics in Kholm region led by bishop Markell (Popel) in 1875.

- In 1890, the Uniate priest Alexis Toth initiated in the USA a process of reunification in which some 90 thousand Greek-Catholic clergy and laity – emigres from Galicia and the Carpathian Rus – reunited with the Mother Church.

- "It was natural that in May 1945, immediately after the victorious end of the Great Patriotic War, an Initiative Group for Reunification of the Greek-Catholic Church with the Russian Orthodox Church was formed to implement the idea for which Father Gabriel suffered so much."

- ↑ Taking part in the Divine service and in the conference were hierarchs of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church: Archbishops Onuphry of Chernigov and Bukovina, Niphont of Lutsk and Volyn, Augustine of Lvov and Drogobych, Sergy of Ternopol and Kremenets, Bishops Methodius of Khust and Vinogradov, Simeon of Vladimir-Volynsky and Koval, representatives of the theological schools from Moscow, Kiev, Lutsk, Pochaev and Warsaw, clergymen from the Rovno, Khust, Chenovtsy; Vladimir-Volynsky and Brest dioceses, Abbess Mikhaila Zaets, mother superior of the Gorodets convent, representatives of the Union of Orthodox Brotherhoods in Ukraine, and many parishioners.

- ↑ "According to our procedure of canonization, a martyr really had to suffer for Christ or for the Church, but not to die by chance. Moreover he shouldn't be a heretic or a schismatic. As for the pious, the Reverend Fathers, there should be the sanctity of life and authority. Kostelnik is somewhere in between a martyr and a pious," the Archbishop said.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Russian Orthodox Church: Official Website of the Department for External Church Relations. 50th anniversary of the martyrdom of Protopresbyter Gabriel Kostelnik. 8.12.1998.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Bohdan R. Bociurkiw. Kostelnyk, Havryil. Encyclopedia of Ukraine, Vol. 2 (1989).

- ↑ Vladimir Moss. Orthodoxy and the Unia in East-Central Europe. March 30 / April 12, 2011.

- ↑ Orthodox England. Hieromartyr Gabriel of Galicia (1886-1948): A Carpatho-Russian Martyr for Christian Unity in Western Russia. St John's Orthodox Church, Colchester.

- ↑ Rev. Christopher Lawrence Zugger. "The Forgotten: Catholics of the Soviet empire from Lenin through Stalin." Syracuse University Press, 2001. p.423.)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Interfax-Religion. The initiator of elimination of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church could be canonized. 23 September 2008, 12:16.

- ↑ (Russian) Из мемуаров Петра Судоплатова. «Военная Литература» Мемуары: Глава 8. «Холодная война» - Дорога к Ялте и начало мирного противостояния.

- ↑ (Russian) Журнал Московской Патриархии. 1948, № 10, стр. 9.

- ↑ Havriil Kostelnik (1886-1948).

Sources

- Orthodox England. Hieromartyr Gabriel of Galicia (1886-1948): A Carpatho-Russian Martyr for Christian Unity in Western Russia. St John's Orthodox Church, Colchester.

- Russian Orthodox Church: Official Website of the Department for External Church Relations. 50th anniversary of the martyrdom of Protopresbyter Gabriel Kostelnik. 8.12.1998.

- Interfax-Religion. The initiator of elimination of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church could be canonized. 23 September 2008, 12:16.

- Bohdan R. Bociurkiw. Kostelnyk, Havryil. Encyclopedia of Ukraine, Vol. 2 (1989).

- Vladimir Moss. Orthodoxy and the Unia in East-Central Europe. March 30 / April 12, 2011.

- Rev. Christopher Lawrence Zugger. "The Forgotten: Catholics of the Soviet empire from Lenin through Stalin." Syracuse University Press, 2001.

- Havriil Kostelnik (1886-1948).

Other languages

- (Ukrainian)

"Украина православна". Биография отца Г. Костельника. Пресс-служба Украинской Православной Церкви. 01.03.2006.

- (Russian)

(Pravoslavie.e-brest.net): Иващук Андрей. Львовский церковный собор 1946 года. Протопресвитер Гавриил Костельник. Православный информационный ресурс. Сергиев Посад 2004.

- (Russian)

(Vestnik article): Андрей ДРАНЕНКО. Протопресвитер Гавриил Костельник и Львовский Собор 1946 года. Вестник, 2006, № 1.

- (Russian)

Russian Wikipedia: Костельник, Гавриил Фёдорович.

- (Serbian)

Serbian Wikipedia: Хавријил Костељник.

Categories > Church History

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > People > Clergy > Priests

Categories > People > Converts to Orthodox Christianity

Categories > People > Converts to Orthodox Christianity

Categories > People > Converts to Orthodox Christianity from Roman Catholicism

Categories > People > Saints > Martyrs