Labarum

The Labarum (Greek: λάβαρον / láboron) was a Christian imperial standard incorporating the sacred "Chi-Rho" Christogram, which was one of the earliest forms of christogram used by Christians, becoming one of the most familiar and widely used emblems in Chrisitan tradition. It was adapted by emperor Saint Constantine the Great after receiving his celestial vision and dream, on the eve of his victory at the Milvian Bridge in 313 AD.

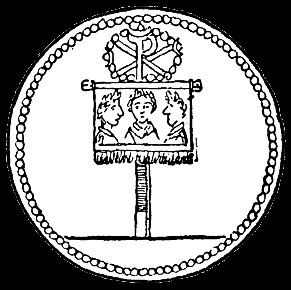

The Labarum of Constantine was a vexillum[note 1] that displayed the "Chi-Rho" Christogram, formed from the first two Greek letters of the word "Christ" (Greek: ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ, or Χριστός) — Chi (χ) and Rho (ρ). Fashioned after legionary standards, it substituted the form of a cross for the old pagan symbols, and was surmounted by a jewelled wreath of gold containing the monogram of Christ, intersecting Chi (χ) and Rho (ρ); upon this hung a rich purple banner,[note 2] beset with gold trim and profuse embroidery. The inscription "Εν Τουτω Νικα" (In Hoc Signo Vinces) — "In this sign, conquer" was in all probability inscribed upon the actual standard, although Eusebius mentions that royal portraits of Constantine and his children were integrated.[note 3] St. Ambrose of Milan later wrote that the Labarum was consecrated by the Name of Christ.[1]

As a new focal point for Roman unity, the monogram appeared on coins, shields, and later public buildings and churches.[2] From 324 the Labarum with the "Chi-Rho" Christogram was the official standard of the Roman Empire.

Contents

Origins

The Labarum was originally a Roman military ensign, which is described to have been a more distinguished form of the Vexillum, or cavalry standard. The vexilloid of the Roman Empire was a red banner with the letters SPQR in Gold surrounded by a gold wreath, hung on a military standard topped by the Roman eagle (or an image of the goddess Victoria) made of silver or bronze.

That the Labarum dated its designation as the imperial standard from an early period of the empire, is confirmed by a colonial medal of Tiberius (dedicated to that Prince by Caesarea-Augusta (Saragozza)), on which may be discerned the form of that ensign. The Labarum is also to be found in the left hand of emperors; on some military figures; and on coins of Nero, Domitian, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, Septimius Severus, and other princes anterior to Constantine. Several colonial coins also show a vexillum or cavalry standard, resembling the Labarum, such as those from Acci, Antiochia Pisidiae, and Caesarea-Augusta.[3]

Like the other standards, it was an object of religious veneration amongst the soldiers, who paid it divine honours. As an imperial standard, the labarum was only hoisted when the Emperor was with the army.

Etymology

The etymology of the word labarum is uncertain, however it has been suggested that the word descended from the Greek láboron (λάβαρον - laurel-leaf standard),[note 4] which in turn renders the Latin Laureum Vexillum, literally "laureled standard".[4][5][6]

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.) states that the word labarum is Late Latin, probably being an alteration of the Greek labraton ("laurel-leaf standard"), which is itself derived from the Latin Laureatum (the neuter of Laureatus - "crowned/adorned with laurel").[7]

It may also be derived from the Latin /labāre/ 'to totter, to waver', in the sense of the "waving" of a flag in the breeze.

Other proposals include a derivation from the Celtic llafar ("eloquent"), or from the ancient Cantabri dialect labaro ('four heads'),[note 5] an ancient Celtic symbol taken by the Legions during the Cantabrian Wars.

Vision of Constantine

It is commonly stated that on the evening of October 27, 312, with his army preparing for the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the emperor Constantine I had a vision which led him to fight under the protection of the Christian God. The details of that vision, however, differ between the sources reporting it, namely those of Lactantius and Eusebius of Caesarea.

Lactantius

Lactantius states[8] that, in the night before the battle, Constantine was commanded in a dream to "delineate the heavenly sign on the shields of his soldiers". He obeyed and marked the shields with a sign "denoting Christ". Lactantius describes that sign as a "staurogram", or a Latin cross with its upper end rounded in a P-like fashion (i.e. a "Tau-Rho" Christogram).[note 6]

Eusebius

From Eusebius of Caesarea, two accounts of the battle survive. The first, shorter one in the Ecclesiastical History leaves no doubt that God helped Constantine. In this version the emperor saw the vision in Gaul on his way to Rome, long before the battle with Maxentius: the phrase as he gives it was: "Εν τουτο νικα" — literally, "In this, win!"[9]

In Eusebius' later Life of Constantine, Eusebius gives a detailed account of a vision and stresses that he had heard the story from the emperor himself.[note 7] According to this version, Constantine with his army was marching somewhere[note 8] when he looked up to the sun and saw a "cross of light" imposed above it, and with it, the Greek words: "Εν Τουτω Νικα" (Latin: in hoc signo vinces — "In this sign, conquer"). Not only Constantine, but the whole army saw the miracle. At first he was unsure of the meaning of the apparition, but the following night he had a dream in which Christ explained to him that he should use the sign against his enemies.

Eusebius then continues to describe the labarum, the military standard used by Constantine in his later wars against Licinius, showing the Chi-Rho sign.[10][note 9]

Eusebius' Description of the Labarum

"A Description of the Standard of the Cross, which the Romans now call the Labarum."

"Now it was made in the following manner. A long spear, overlaid with gold, formed the figure of the cross by means of a transverse bar laid over it. On the top of the whole was fixed a wreath of gold and precious stones; and within this, the symbol of the Saviour’s name, two letters indicating the name of Christ by means of its initial characters, the letter P being intersected by X in its centre: and these letters the emperor was in the habit of wearing on his helmet at a later period. From the cross-bar of the spear was suspended a cloth, a royal piece, covered with a profuse embroidery of most brilliant precious stones; and which, being also richly interlaced with gold, presented an indescribable degree of beauty to the beholder. This banner was of a square form, and the upright staff, whose lower section was of great length, of the pious emperor and his children on its upper part, beneath the trophy of the cross, and immediately above the embroidered banner." "The emperor constantly made use of this sign of salvation as a safeguard against every adverse and hostile power, and commanded that others similar to it should be carried at the head of all his armies."[11]

Fifty soldiers of the imperial guard (ὑπασπισταἰ), distinguished for bravery and piety, were entrusted with the care and defense of the new sacred standard, which was to be borne by them singly by turns (Vita Constant., II:8). Standards, similar to the original labarum in its essential features were supplied to all the legions, and the monogram was also engraved on the soldiers' shields.[12]

Historical Evidence for Use of the Labarum

Historians contend that the accounts of Lactantius and Eusebius can hardly be reconciled with each other, though they have been merged in popular notion into Constantine seeing the Chi-Rho sign on the evening before the battle.

There is no certain evidence of the use of the letters chi and rho as a Christian sign before Constantine. Its first appearance is on a Constantinian silver coin from ca. 317, which proves that Constantine did use the sign at that time, though not very prominently.[13] He made extensive use of the Chi-Rho and the labarum only later in the conflict with Licinius.

In the course of Constantine's second war against Licinius in 324, the latter developed a superstitious dread of Constantine's standard. During the attack of Constantine's troops at the Battle of Adrianople, the guard of the labarum standard were directed to move it to any part of the field where his soldiers seemed to be faltering. The appearance of this talismanic object appeared to embolden Constantine's troops and dismay those of Licinius.[14] At the final battle of the war, the Battle of Chrysopolis (324), Licinius, though prominently displaying the images of Rome's pagan pantheon on his own battle line, forbade his troops from actively attacking the labarum, or even looking at it directly.[15]

Eusebius stated that in addition to the singular labarum of Constantine, other similar standards (labara) were issued to the Roman army. This is confirmed by the two labara depicted being held by a soldier on a coin of Vetranio dating from 350.

The sacred symbols were naturally removed from the standards by Julian the Apostate, but were restored by Jovian and his successors, and continued to be borne by later Byzantine emperors.[16] The Labarum marked with the monogram of Christ is seen on the coins of Constantine the Great, and also of Constans, of Jovian, and of Valentinian, to the end of the imperial series.[17]

Later Usage

Later usage came to regard the terms "Labarum" and "Chi-Rho" as synonymous, although ancient sources draw an unambiguous distinction between the two due to their separate origins.

Christians' use of the sacred "Chi-Rho" Christogram naturally expanded into a variety of other areas and formats as well. This included on coins and medallions (minted during Constantine's reign and by subsequent rulers, becoming part of the official imperial insignia after Constantine); on Christian sarcophagi and frescoes from about 350 AD; and eventually appearing on public buildings and churches as well.

A later Byzantine manuscript indicates that a jewelled Labarum standard believed to have been that of Constantine the Great was preserved for centuries, as an object of great veneration, in the imperial treasury at Constantinople.[18] The Labarum, with minor variations in its form, was widely used by the Christian Roman emperors who followed Constantine. A miniature version of the Labarum became part of the imperial regalia of Byzantine rulers, who were often depicted carrying it in their right hands.

In the Middle Ages the pastoral staff of a bishop often had attached to it a small purple scarf known as the vexillum, supposedly derived from the Labarum.[19] The Chi-Rho monogram is also found on Eucharistic vessels and lamps.[20]

In Greece, the "Holy Lavara" were a set of early national Greek flags, blessed by the Greek Orthodox Church. Under these banners the Greeks united throughout the Greek War of Independence (1821-32), a war of liberation waged against the Ottoman Empire.[note 10]

Today, the term "Labarum" is generally used for any ecclesiastical banner, such as those carried in religious processions.[note 11]

Gallery

Constantius II. (350-351 AD). Inscribed with "HOC SIGNO VICTOR ERIS" (In this sign, conquer), and Constantius holding the Labarum (Chi-Rho Christogram standard), similar to Constantine's vision.

Coin of Magnentius (350-353 AD) with a large Chi-Rho, showing the first apparent use of the Alpha and Omega flanking the Christogram.

Anastasis, symbolic representation of the resurrection of Christ, (Sarcophagus, ca. 350 AD).

Monogram of Christ within a wreath, including the Alpha and Omega.

(Museo Pio Cristiano, Vatican, undated).The Hinton St Mary Mosaic, mid 4th-c., featuring a portrait bust of Jesus Christ with the Chi-Rho symbol as its central motif.

Mosaic of Emperor Justinian with his retinue, with the Labarum displayed on a soldier's shield. (Ravenna, before 547 AD).

The Book of Kells, Folio 34r, containing the Chi-Rho Monogram (ca. 800 AD).

Bp. Germanos of Old Patras blessing the Greek banner (Labaro / Λάβαρο) at Agia Lavra monastery, March 13, 1821.

Modern ecclesiatical Labara from the Roman Catholic Abbey Church of St. Verena, Rot an der Rot, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

A modern Orthodox ecclesiastical standard (Labarum), with icon of Christ.

Theophany procession on the San River (southeastern Poland / western Ukraine).

See also

Notes

- ↑ The vexillum (plural vexilla) was a military standard (flag, banner) used in the Classical Era of the Roman Empire. On the vexillum the cloth was draped from a horizontal crossbar suspended from the staff; this is unlike most modern flags in which the 'hoist' of the cloth is attached directly to the vertical staff. The bearer of a vexillum was known as a vexillarius. The vexillum was a treasured symbol of the military unit that it represented and it was closely defended in combat.

- ↑ Purple dye at this time was a rarity derived from a shellfish of the genus Murex. Tyrian purple ((Greek, πορφύρα, porphyra, Latin: purpura), also known as royal purple, imperial purple) was prized by the Romans, who used it to colour ceremonial robes.

- ↑ These portraits could have been embroidered, or set as medallions/roundels on the staff. Later, the name Labarum was given to variants of the original standard. An idea of some of the deviations in form of the standards furnished to different divisions of the army may be obtained from several coins of Constantine's reign that are still preserved. On one coin, for instance, the portraits of the emperor and his sons are represented on the actual banner (instead of as medallions/roundels on the staff); on a second, the banner is inscribed with the Chi-Rho monogram, and surmounted by the equal-armed cross while the medallions/roundels of the royal portraits, are on the shaft below the banner. ("Labarum." Original Catholic Encyclopedia).

- ↑ The similar Greek term "Lavra" has a different etymology. In Orthodox Christianity and certain other Eastern Christian communities Lavra or Laura (Greek: Λαύρα; Cyrillic: Ла́вра) originally meant a cluster of cells or caves for hermits, with a church and sometimes a refectory at the center (for example, Agia Lavra monastery in Greece). The term originates from Ancient Greek, where it means "a passage" or "an alley".

- ↑ In modern Basque the word is lauburu, with the same meaning.

- ↑ Dr. Larry Hurtado has stated that contrary to some widely influential assumptions, this "Tau-Rho" staurogram appears to be the earliest of the Christograms, and not the more familiar "Chi-Rho". He writes that the earliest extant Christian use of the "Tau-Rho" is not as a freestanding symbol and general reference to Christ, but in manuscripts dated as early as around 175-225 AD, where it functions as part of the abbreviation of the Greek words for "cross" (σταυρός) and "crucify" (σταυρόω), written (abbreviated) as nomina sacra. (Hurtado, L.W. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Cambridge, 2006. p.136.)

- ↑ Of the miracle, Eusebius wrote in the Vita that Constantine himself had told him this story "and confirmed it with oaths," late in life "when I was deemed worthy of his acquaintance and company." "Indeed," says Eusebius, "had anyone else told this story, it would not have been easy to accept it."

- ↑ Eusebius doesn't specify the actual location of the event, but it clearly isn't in the camp at Rome.

- ↑ Among the many soldiers depicted on the Arch of Constantine, which was erected just three years after the battle, the labarum does not appear, nor is there any hint of the miraculous affirmation of divine protection that had been witnessed, Eusebius maintains, by so many. Its inscription does say that the emperor had saved the res publica INSTINCTU DIVINITATIS MENTIS MAGNITUDINE ("by greatness of mind and by instinct [or impulse] of divinity"). Which divinity is not identified, though Sol Invictus — the Invincible Sun (also identifiable in Apollo or Mithras) — is inscribed on Constantine's coinage at this moment. (Labarum. EconomicExpert.com.)

- ↑ The blessing of the standards recalls Constantine's use of the Labarum with the Chi-Rho Christogram before his battle with Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge, just over 1500 years earlier.

- ↑ Some Protestant Christians (especially Restorationists) reject the use of Labarum Christogram due to its supposed pagan origins and lack of use by the earliest Christians. Supporters point out that use of the Labarum was in widespread use by Christians by the mid-fourth century, mostly on sarcophagi.

References

- ↑ Ambrose of Milan. "Letter XL." St. Ambrose Selected Letters.

- ↑ -----. "Labarum." In: J.D. Douglas and Earle E. Cairns (Eds.). The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church. 2nd ed.. Zondervan Publishing House, 1996. p.575.

- ↑ Labarum. Numiswiki: The Collaborative Numismatics Project.)

- ↑ H. Grégoire, "L'étymologie de 'Labarum'" Byzantion 4 (1929:477-82).

- ↑ Kahane, Drs. Henry & Renée. "Contributions by Byzantinologists to Romance Etymology." RLiR, XXVI (1962), 126-39.

- ↑ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed.. Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press, 1991. p.1167.

- ↑ "Labarum". The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, copyright ©2000 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Updated in 2009. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ↑ Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors, chapter 44.5.

- ↑ Labarum. EconomicExpert.com.

- ↑ Gerberding and Moran Cruz, 55; cf. Eusebius, Life of Constantine.

- ↑ Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine, Chapter XXXI.

- ↑ Hassett, Maurice. "Labarum (Chi-Rho)." The Catholic Encyclopedia. (New Advent). Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.

- ↑ Smith, 104: "What little evidence exists suggests that in fact the labarum bearing the chi-rho symbol was not used before 317, when Crispus became Caesar..."

- ↑ Odahl, p. 178.

- ↑ Odahl, p.180

- ↑ Smith, Sir William and Samuel Cheetham (eds.). "Labarum." A dictionary of Christian antiquities: Being a continuation of the ʻDictionary of the Bible', Volume 2. J. B. Burr, 1880. p.910.

- ↑ Labarum. Numiswiki: The Collaborative Numismatics Project.

- ↑ Lieu and Montserrat p. 118. From a Byzantine life of Constantine (BHG 364) written in the mid to late ninth century.

- ↑ "Labarum." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- ↑ -----. "Chi Rho (XP)." In: Steffler, Alva William. Symbols of the Christian Faith. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. p.66.

Sources and further reading

- -----. "Labarum." In: J.D. Douglas and Earle E. Cairns (Eds.). The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church. 2nd ed.. Zondervan Publishing House, 1996. p.575.

- -----. "Labarum". The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, copyright ©2000 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Updated in 2009. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company.

- -----. "Labarum." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- -----. Labarum. Wikipedia.

- -----. Labarum. Numiswiki: The Collaborative Numismatics Project.

- -----. Labarum. New World Encyclopedia.

- -----. Labarum. EconomicExpert.com.

- -----. Labarum. Original Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Grabar, Andre. Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins. Princeton University Press, 1981.

- Grant, Michael. The Emperor Constantine. London, 1993.

- Hassett, Maurice. "Labarum (Chi-Rho)." The Catholic Encyclopedia. (New Advent). Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.

- Hurtado, L.W. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Cambridge, 2006.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed.. Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press, 1991. p.1167. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- Lieu, S.N.C and Montserrat, D. (Eds.). From Constantine to Julian. London, 1996.

- Odahl, C.M. Constantine and the Christian Empire. Routledge 2004.

- Paap, A. H. R. E. (Prof.). Nomina Sacra in the Greek Papyri of the First Five Centuries. Papyrologica Lugduno-Batava, Volumen VIII, Leiden, 1959.

- Pitt-Rivers, George Henry Lane Fox . The Riddle of the 'Labarum' and the Origin of Christian Symbols. Allen & Unwin, 1966.

- Smith, J.H. Constantine the Great. Hamilton, 1971.

- Steffler, Alva William. Symbols of the Christian Faith. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002.

- Smith, Sir William and Samuel Cheetham (eds.). "Labarum." A dictionary of Christian antiquities: Being a continuation of the ʻDictionary of the Bible', Volume 2. J. B. Burr, 1880. pp.908-911.

External Links

Wikipedia

- Chi Rho

- Christogram

- Christian symbolism

- Chrismon

- Constantine I and Christianity

- Christianity and Paganism

- Early Christian inscriptions

- Idolatry and Christianity

- IX monogram

- Labarum

- Nomina sacra

- Talisman

- The Vision of the Cross

Other