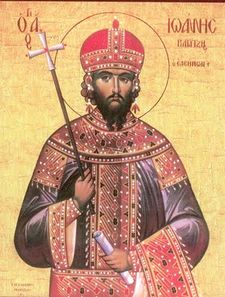

John III Doukas Vatatzes

Emperor Saint John Vatatzes the Merciful ((Greek)

- Ὁ Ἅγιος Ἰωάννης ὁ Βατατζὴς ὁ ἐλεήμονας βασιλιὰς[1]), also John III Doukas Vatatzes ((Greek)

- Ιωάννης Γ΄ Δούκας Βατάτζης) or John III Vatatzes, was the Emperor of Nicaea[note 1] from 1221 to 1254 and one of the most remarkable among the successors of Constantine the Great, being the chief architect of the restored Byzantine Empire, and a respected leader who encouraged justice, charity and a cultural blossoming. He was born ca.1192 in Didymoteicho and died on 3 November 1254 in Nymphaion. His feast day is on November 4.[1][note 2]

Contents

- 1 Biography

- 1.1 Early Life

- 1.2 Founding of Empire of Nicaea

- 1.3 Relations with Bulgaria

- 1.4 Relations with the Holy Roman Emperor

- 1.5 Recovery of Southern Balkans

- 1.6 Relations with the Papacy

- 1.7 Relations with the Sultanate of Rum

- 1.8 Internal Policy and Social Structures

- 1.9 Patron of the Arts and Sciences

- 1.10 Death

- 2 Legacy

- 3 Relics and Veneration

- 4 Legend of the Reposed King

- 5 Hymns

- 6 See also

- 7 Notes

- 8 References

- 9 Sources

- 10 External Links

Biography

Early Life

John Doukas Vatatzes was probably the son of the general Basil Vatatzes, Domestikos of the East, who died in 1193, and his wife, an unnamed niece of the Emperors Isaac II Angelos and Alexios III Angelos.[note 3]

The Vatatzes were a great military family of Thrace. They had representatives in the senate and were related to other eminent families, like the Doukes, the Angeloi and the Laskarids.[2] The Vatatzes family had first become prominent in Byzantine society in the Komnenian period and had forged early imperial connections when Theodore Vatatzes married the porphyrogenete princess Eudokia Komnene, daughter of Emperor John II Komnenos.

Founding of Empire of Nicaea

Following the capture of Constantinople in 1204, John Doukas Vatatzes went to Nymphaeum in Asia Minor, which Theodore I Laskaris (1207/8-1222) had chosen as the seat of the Byzantine Empire of Nicaea. Thanks to the intercession of an uncle of his who was a priest in the palace and an associate of the emperor, John Vatatzes entered the emperor’s service. The emperor appreciated his talents and his moral fibre, and conferred upon him the title of Protovestiarios.[2]

Next to this distinguished prince, Vatatzes was the most active and successful in preventing the whole of the Greek empire from becoming a prey to the Latins, and he was likewise one of those who supported Theodore Lascaris after he had assumed the imperial title, and taken up his residence at Nicaea. In reward for his eminent services in the field as well as in the council, in 1212 Theodore gave him the hand of his daughter Irene Laskarina, and appointed him his future successor. Having no children, Theodore I Laskaris thought Vatatzes more fit and worthy for the crown than either of his four brothers, Alexis, John, Manuel, and Michael.[3] However as this arrangement excluded members of the Laskarid family from the succession, when John III Doukas Vatatzes became emperor in mid-December 1221,[4] he had to suppress opposition to his rule.

In January 1222 John Vatatzes was crowned emperor by Patriarch Manuel I (Charitopoulos) of Constantinople. His wife Irene gave birth to only one son, the heir Theodore II Lascaris in 1222.[note 4]

Meanwhile, in 1224 Theodore Komnenos Doukas, the ruler of Epirus and Thessaly, made himself master of Thessalonica and of nearly the whole of Macedonia, assumed the title of emperor, and was crowned by the Autonomous Archbishop of Achrida[3] Demetrios Chomatianos. Four emperors now reigned over the remnants of the Eastern empire:

- Andronicus I Gidos in Trebizond (1222-1235),

- Theodore Komnenos Doukas in Epirus and Macedonia (1215-1230),

- Robert of Courtenay in Constantinople (1221-1228), and

- John Vatatzes in Nicaea (1221-1254).[3]

Battle of Poimanenon (1224)

No sooner has Vatatzes ascended the throne than Manuel and Michael Lascaris abandoned him, went to Constantinople, and persuaded Robert of Courtenay to declare war against Vatatzes. Its result was unfavourable to the Latins. In the pitched Battle of Poimanenon in 1224, the Latin troops were completely defeated; and such was the hatred of the Greeks against the foreign intruders, that they neither gave nor accepted quarter: the two Lascarids were taken prisoners, and paid their treason with the loss of their eyes. In consequence of this victory, the greater part of the Latin possessions in Asia fell into the hands of the Greeks. On the sea the Latins were successful; they blockaded the Greek fleet in the port of Lampsacus, and Vatatzes preferred burning his own ships to having them burnt by his enemy. However, Vatatzes had little to lose on the sea, and the Latin emperor was finally compelled to sue for peace, and to leave the greater part of his Asiatic possessions in the hands of Vatatzes.[3]

The peace was of short duration. The old John of Brienne (1231-1237), who after the death of Robert, in 1228, exchanged his nominal Kingdom of Jerusalem for the real though tottering throne of Constantinople, attacked Vatatzes in 1233, in Asia, but was routed in Bithynia, and hastened back to Thrace. Supported by the fleets of the Venetians, he could, however, renew his inroads whenever he saw a favourable opportunity.

Accordingly, Vatatzes conceived the plan of making himself master of the sea.[note 5] He expanded Nicaean control over much of the Aegean and annexed the important island of Rhodes, as well as Samos, Lesbos, Chios, Cos and many other islands. However the main force of the Venetians was in Candia (Crete); and although Vatatzes conquered the greater part of that island (Crete), his progress was checked by the Venetian governor Marino Sanuti, the historian, who at last forced the Greeks to sail back to Asia.[3]

Relations with Bulgaria

Initially Ivan Asen II and John Vatatzes were on opposite sides, each seeking to capture Constantinople for his own sake. However the political developments in the Latin Empire of Constantinople and the ascension of John de Brienne to the imperial throne created ideal conditions for rapprochement between the Nicaean state and the Bulgarian one.[2]

Siege of Constantinople (1235)

Ivan Asen appeared on the side of Vatatzes as the inciter of an anti-Latin alliance of Orthodox rulers, to which Manuel of Thessalonica also acceded. In the context of the negotiations, the political and ecclesiastical leadership of Nicaea accepted the founding of a Bulgarian patriarchate (1235), as long as it recognized the sovereign authority of the Nicaean patriarchate. In the spring of 1235 the alliance was signed in Kallipolis, which was soon after sealed with the marriage of John Vatatzes’ son and heir, Theodore, to the daughter of Ivan Asen, Helen. The allies immediately commenced hostilities against the Latins and besieged Constantinople by land and sea. The Latin Empire was restricted to a small strip of land around Constantinople. The siege, however, was unsuccessful.[2] The superiority of the Latin mariners over the Greek led to a total defeat of the Greek fleet, and twenty-four Greek gallies fell into the hands of the victors, and were paraded in triumph in the port of Constantinople. By land, however, Vatatzes was more successful, and conquered the rest of the Latin possessions in Asia.[3]

Siege of Constantinople (1236)

In 1236 the allies attempted to capture the capital once again. During the siege, however, Asen, fearsome of the rise of Nicaea, and listening to the persuasions of Anseau de Cayeux, who acted as regent in the absence of the emperor Baldwin II (1237-1261), cancelled the alliance and demanded that his daughter, Helen, should return to him. He then sided with the Latins and the Cumans of Macedonia and, circa 1237, he commenced hostilities against Vatatzes, besieging Tzouroulos, a strategic stronghold. During that siege Ivan Asen changed his mind again, and remorseful, he broke off the siege, sent his daughter Helen back to Nicaea, and signed a peace treaty with Vatatzes. In 1241 the Bulgarian ruler passed away. Then John III Vatatzes, rid of all of his dangerous enemies, renewed the pact with the underage heir of Ivan Asen, Kaliman Asen I (1241-1246).[2]

Relations with the Holy Roman Emperor

In the West John Vatatzes’ main diplomatic concern was a rapprochement with the German emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen and an alliance with him, as both rulers were united in their struggle against the Latins. Frederick supported the Byzantine efforts to capture Constantinople and in 1236 he cancelled the crusade that Pope Gregory IX was organizing against Vatatzes, on account of John III’s hostilities against the Latins. John Vatatzes in turn sided with Frederick in the latter’s feud with the Pope. Later the two rulers signed an alliance, and in 1244 Vatatzes took as his spouse Constance, the illegitimate daughter of the German emperor, who subsequently took on the name Anna. This alliance, however, brought no significant gain to the Empire of Nicaea, although Vatatzes maintained diplomatic relations with the German dynasty even after the death of Frederick, during the reign of Conrad IV (1250-1254).[2]

Recovery of Southern Balkans

The assistance which the Latin emperor Baldwin II obtained in Europe is mentioned in the life of that emperor; but the formidable knights of France and Italy tried in vain to obtain a firm footing in Asia, and Baldwin was reduced to such weakness, that he was unable to prevent Vatatzes from sailing over to Macedonia, and compelling the self-styled emperor, John Comnenus (1237-1242), to cede to him Macedonia, to renounce the imperial title, and to be satisfied with that of despot of Epirus.[3] Thus he was able to establish his suzerainty over Thessalonica in 1242, and later to annex this city.

By 1246, following the death of the Bulgarian tsar Kaliman, successor to Ivan Asen, John Vatatzes expanded his dominion in the Balkan Peninsula. After capturing the cities of Serres, Meleniko, Velbuzd, (modern Kyustendil), Skopje, Velesa, Pelagonia and Prosakos, he expanded his domain in Thrace up to the sources of the river Evros and in Macedonia up to the Axios (Vardar) river. Finally he turned west against Demetrios Doukas Angelos, and in December of 1246 he captured Thessalonica, forcing Demetrios to submit.[2]

Around 1247-1248, the forces of Nicaea campaigned in Thrace, capturing Tzouroulos and Vizye, thus establishing an effective stranglehold on Constantinople.[2] Vatatzes took several of the towns of the Latins in Thrace, and made peace with Michael in 1253.[3]

Relations with the Papacy

The first contacts between Nicaea and the Papacy took place in Nicaea in 1232. In 1234, delegates of the two churches met first at Nicaea and then at Nymphaeum. They negotiated the issues related to the union of the Churches. Dogmatic issues were also discussed in depth. The Orthodox clerics, Nikephoros Blemmydes being their main representative, rejected the Latin teaching on the purgatorial fire. Finally the talks came to a dead end. In 1236, on the occasion of the hostilities of the alliance of the Byzantines and the Bulgrarians against the Latins of Constantinople, Nicaean relations with the Vatican deteriorated, and Pope Gregory IX issued a crusading bull authorizing a crusade against the Byzantines.[2]

Relations with the Sultanate of Rum

In 1242 the Mongols invaded Asia Minor threatening to destroy the Empire of Trebizond and the Sultanate of Rum, causing great upheaval in the region. Therefore in 1243 Vatatzes concluded an alliance with Gaiyath-ed-din, the Turkish Sultan of Iconium, in order to resist the approaching Mongols.[note 6] Having thus secured his eastern frontiers, he was able to concentrate upon the Balkan peninsula and obtained brilliant results.

In connection with the Mongol (Tartar) invasion, a story is given by a western historian of the thirteenth century, Matthew of Paris, stating that in 1248 two Mongol envoys were sent to the Papal court and were cordially received by Pope Innocent IV, who hoped to convert the Mongols to Christianity. In his Historia Anglorum Matthew said that the Pope directed the Mongol envoys to notify the king of the Tartars, that if the latter had adopted Christianity, he should march with all his troops upon John Vatatzes, "a Greek, son-in-law of Frederick, schismatic, and rebel against the Pope and Emperor Baldwin, and after that upon Frederick himself who had risen against the Roman curia."[5] The Mongols rejected the papal plan on the ironical pretense that they were loath to encourage "the mutual hatred of Christians."[6] However, Byzantine historian A. A. Vasiliev has concluded that this story cannot be treated as historical fact, reflecting instead a type of thirteenth century European gossip; although adding that the political power and importance of John Vatatzes was widely and thoroughly appreciated, and played a certain part, at least in the opinion of western European writers, in the negotiations between the Pope and the Mongol envoys.[5]

Internal Policy and Social Structures

His policy of appointing people of non-aristocratic descent in administrative posts was ground-breaking, causing much resentment among members of the aristocracy, noting that he relied heavily on the support of the military aristocracy. The success of his internal policy, however, was mainly the result of his economic and agrarian measures, which aimed at achieving economic self-sufficiency and the improvement of domestic production, as well as at diminishing the import of foreign products, especially western luxury goods.[2]

In his social policy, he took steps to improve the living standards of rural and city people. He conducted a census and bestowed on each subject of the empire a plot of land. Towards the end of his administration, he also requisitioned movable and immovable property belonging to great land-owners and the nobility, thus causing their disgruntlement. According to the sources he led a very frugal life, and took additional measures to curtail excessive spending of private wealth. Moreover, in order to firmly establish social justice in his state, he took measures against the exploitation of the poor.[2]

In the context of his wider social policy, John Vatatzes also saw after the smoother function of the Church. In 1228 he issued a chrysobull (decree) in which he forbade the interference of political authorities into ecclesiastical inheritance. He also made generous donations to ecclesiastical institutions and saw to the rebuilding of the existing temples and the construction of new ones, like the Monastery of Sosandra on Mt. Sipylos in Magnesia (founded in 1224), and the Monastery of Lemvos in Smyrna.[2]

Patron of the Arts and Sciences

In periods of peace Vatatzes employed his leisure in promoting the happiness of his subjects. He patronized arts and sciences, constructed new roads, distributed the taxes equally, and made himself beloved by every body through his kindness and justice.[3] He was greatly interested in the collection and copying of manuscripts. The foremost representative of the educational movement of the 13th century, the scholar, writer and teacher Nikephoros Blemmydes, lived during his reign. Among Blemmydes’ students were Vatatzes' heir, the learned Theodore II Laskaris, as well as the historian and statesman George Akropolites. The sources abound with references to the emperor's great concern for the development of his state’s intellectual life. He promoted the creation of centres of learning, especially of secular studies, while higher educational institutions were organized.[2]

Death

About 1252 when Michael of Epirus (1230-1268) threatened a new war, Vatatzes set out against him, but was taken ill at Macedonia and returned to Asia. He died after long sufferings at Nymphaeum on November 3rd 1254 at the age of sixty-two, ending a reign of thirty-three (33) years. He was buried in the Monastery of Christ the Savior (Monastery of Sosandra) on Mt. Sipylos close to Magnesia, in the wider area of Smyrna.

With rare unanimity Byzantine historians unanimously glorify him. His son and successor, Theodore II Lascaris, wrote in a panegyric: “He has unified the Ausonian land, which was divided into very many parts by foreign and tyrannic rulers, Latin, Persian, Bulgarian, Scythian and others, punished robbers and protected his land...He has made our country inaccessible to enemies.” In spite of his epilepsy, John had provided active leadership in both peace and war. And even if there is some exaggeration by the sources in their estimate of the Emperor of Nicaea, John Vatatzes must be considered a talented and energetic politician, and the chief creator of the restored Byzantine Empire.[5]

Legacy

John III Vatatzes (1221-54) is justly called one of the greatest emperors of the East.

His external policy was focused on the recapture of Constantinople and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire.[2] By eliminating gradually the pretenders to the role of restorer of the Empire — the rulers of Thessalonica, Epirus, and Bulgaria — he brought under his power so much territory as practically to signify the restoration of the Byzantine Empire.[5] John III laid the groundwork for Nicaea's recovery of Constantinople, and was successful in maintaining generally peaceful relations with his most powerful neighbors, Bulgaria and the Sultanate of Rüm, while his network of diplomatic relations extended to the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy, and his armed forces included Frankish mercenaries. Consequently, the merit of having put an end to the Latin empire belongs as much to John Vatatzes as to Michael VIII Palaeologus, who carried out in 1261, the plan which had been conceived and successfully begun by him.[3]

Internally, John's long reign was one of the most creditable in history, witnessing the careful development of the internal prosperity and economy of his realm, and encouraging justice and charity and a cultural blossoming. Despite expensive campaigns to restore Byzantine unity, he lowered taxes, encouraged agriculture, built schools, libraries, churches, monasteries, hospitals, and homes for the old or the poor. Literature and art prospered under him, and he took steps to ensure the harmonious coexistence of the State with the Church, so that Nicaea became one of the richest, fairest cities of the thirteenth century.[6]

The generations after John Vatatzes looked back upon him as “the Father of the Greeks.”[5][note 7]

Relics and Veneration

Seven years after his death when his grave was opened, a sweet fragrance permeated the surroundings, and they were surprised to find that his body was incorrupt, a clear example of holiness. His relics showed no sign that he was in fact dead; the color of his body was like that of a living person, and even his clothes had not deteriorated after 7 years and looked like they had just been newly sewn.[7]

A half-century after his death, John Vatatzes was so beloved and esteemed by the people that he was commemorated as a saint under the name John the Merciful.[1][8] George Akropolites mentions that the people saw to the construction of a temple in his honour in Nymphaeum, and that his cult as a saint quickly spread to the people of western Asia Minor.[2]

Miracles began to be connected with his memory and The Life of St. John the Merciful was composed, a sort of popular canonization. As noted by his biographer, Christians who went on pilgrimage to pray before the Saint were rewarded with miracles; the diseased were healed and demons were expelled at his holy relics.[7] The clergy and population of the Lydian city of Magnesia and its surroundings, where the Emperor was buried (Monastery of Christ the Savior on Mt. Sipylos (Monastery of Sosandra)), gathered annually on November 4 in the local church and honoured the memory of the late Emperor John the Merciful.[5]

The cult of the saintly emperor survived untill the modern years, mainly in the Metropolis of Ephesus. Although the Greek church never formally recognized John Vatatzes as a saint, there is a reference in the Menologia for the commemoration of “John Doukas Vatatzes” on the 4th of November.[2][note 8]

On November 4, 2010 the first and only Orthodox Church in the world was dedicated to St. John Vatatzes, in the city of his birth, Didymoteicho (Metropolis of Didymotichon, Orestias and Soufli).[9]

Legend of the Reposed King

A contemporary account during the reign of Andronikos Palaiologos (1282-1328), mentions that around the time that the Turks invaded Magnesia, on several occasions the castle guardsman had witnessed a lit candle circling around the city walls. He sent men to investigate the phenomenon but to no avail. Then the deaf-mute brother of the guardsman was sent, and he was given a revelation, and was completely healed upon his return. He said that at the area where the lit candle had appeared, he found a man of a grand royal stature, who loudly urged the Christians to continue the defense. Later he recognized the image of the man he had seen when visiting the holy shrine of St. John Vatatzes. Since then John was recognized as a Saint and his memory was set to be honoured on November 4.[7]

His incorrupt relics were transferred to Constantinople, which had been liberated from the Franks, where the legend of the reposed King became associated with him. At time of the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks, his relics were hidden in a catacomb.[7]

The legend states that since that time, he has been awaiting the liberation of Constantinople. It also states that the holy king has his sword with him in its sheath, and that each year the blade of the sword emerges a few millimeters, until the time comes for the entire sword to emerge completely, which will signify the time for the liberation of the City.[7]

A contemporary Elder has said that the Merciful King has already arisen for some time, and that the sword has emerged completely from its sheath. He wanders the City in the form of a fool, and directs the armies of the Saints so as to take their place around the Queen of Cites. The Elder also maintains that the sacred relics of Emperor Saint John Vatatzes the Merciful were guarded by a family of Crypto-Christians, which kept them secret from generation to generation.[7]

Hymns

Nicodemus the Athonite (1749-1809) composed an akolouthia in honour of the emperor-saint John Vatatzes the Merciful, commissioned by the Metropolitan of Ephesus.[2][note 9]

See also

Wikipedia

Notes

- ↑ The Empire of Nicaea was the largest of the three Byzantine Greek successor states founded by the aristocracy of the Byzantine Empire that fled after Constantinople was occupied by Western European and Venetian forces during the Fourth Crusade. Founded by the Laskaris family, it lasted from 1204 to 1261, when the Nicaean recovery of Constantinople re-established the Byzantine Empire.

- ↑ Not be confused with the 7th-century Saint John the Merciful (November 12).

- ↑ John Doukas Vatatzes had two older brothers:

- The eldest was Isaakios Doukas Vatatzes (died 1261), who married and had two children: Ioannes Vatatzes (born 1215), who married to Eudokia Angelina and had two daughters Theodora Doukaina Vatatzaina, wife of Michael VIII Palaiologos, and Maria Vatatzaina, married to Michael Doukas Glabas Tarchaneiotes, Military Goveror of Thrace; and a daughter, married to Konstantinos Strategopoulos. His other older brother was the father in law of Alexios Raul (died 1258).

- The Batatzes family. Emperors of Byzantium. 1 October 2002.

- The eldest was Isaakios Doukas Vatatzes (died 1261), who married and had two children: Ioannes Vatatzes (born 1215), who married to Eudokia Angelina and had two daughters Theodora Doukaina Vatatzaina, wife of Michael VIII Palaiologos, and Maria Vatatzaina, married to Michael Doukas Glabas Tarchaneiotes, Military Goveror of Thrace; and a daughter, married to Konstantinos Strategopoulos. His other older brother was the father in law of Alexios Raul (died 1258).

- ↑ Years later his wife Irene fell from a horse and was so badly injured that she was unable to have any more children. She retired to a convent, taking the monastic name Eugenia, and died there in 1239.

- ↑ Had he succeeded, the Greek empire would have been soon restored to its limits of 1204.

- ↑ Nevertheless after the Battle of Köse Dag in 1243 the Sultan was crushed and the Seljuq Turks were forced to swear allegiance to the Mongols and became their vassals.

- ↑ "Apostolos Vacalopoulos notes that John III Ducas Vatatzes was prepared to use the words ‘nation’ (genos), ‘Hellene’ and ‘Hellas’ together in his correspondence with the Pope. John acknowledged that he was Greek, although bearing the title Emperor of the Romans: “the Greeks are the only heirs and successors of Constantine”, he wrote. In similar fashion John’s son Theodore II, acc. 1254, who took some interest in the physical heritage of Antiquity, was prepared to refer to his whole Euro-Asian realm as “Hellas” and a “Hellenic dominion”. (What Vacalopoulos does not examine is whether, like the Latins, they also called their Aegean world ‘Roman-ia’)."

- Michael O'Rourke. Byzantium: From Recovery to Ruin, A Detailed Chronology: AD 1220-1331. Compiled by Michael O'Rourke. Canberra, Australia, April 2010.

- ↑ According to Vasiliev, the Orthodox calendar gives the name of “John Ducas Vatadzi” under November 4:

- Arch. Sergius. The Complete Liturgical Calendar (Menologion) of the Orient. (2nd ed., 1901), II, 344.

- ↑ For the full service in Greek to St. John Vatatzes the Merciful see:

- (Greek)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Great Synaxaristes: (Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Ἰωάννης ὁ Βατατζὴς ὁ ἐλεήμονας βασιλιὰς. 4 Νοεμβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Banev Guentcho. John III Vatatzes. Transl. Koutras, Nikolaos. Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor (EHW). 12/16/2002.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 William Plate, LL.D. "JOANNES III VATATZES". In: A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. II: EARINUS-NYX. Ed. William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1880. pp. 578-579.

- ↑ George Akropolites. The History. Trans. Ruth Macrides. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, p.160.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 A.A. Vasiliev. History of the Byzantine Empire. Vol. 2. Univeristy of Wisconsin Press, 1971. pp.531-534.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Will Durant. THE AGE OF FAITH: A History of Medieval Civilization - Christian, Islamic, and Judaic - from Constantine to Dante: A.D. 325 - 1300. (The Story of Civilization Series). New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950. pp.651-652.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 (Greek) Ιωάννα Κατσούλα. ΑΓΙΟΣ ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ Ο ΒΑΤΑΤΖΗΣ. Ο μαρμαρωμένος ελεήμων βασιλιάς και η βασιλεύουσα. ΣΤΥΛΟΣ ΟΡΘΟΔΟΞΙΑΣ. ΝΟΕΜΒΡΙΟΣ 2011.

- ↑ George Ostrogorsky. History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1969, p.444.

- ↑ (Greek) Λαμπρά θυρανοίξια του Ι.Ν. Αγίου Ιωάννη Βατάτζη στο Διδυμότειχο. AMEN.gr. Nov 5, 2010.

Sources

- A.A. Vasiliev. History of the Byzantine Empire. Vol. 2. Univeristy of Wisconsin Press, 1971.

- Banev Guentcho. John III Vatatzes. Transl. Koutras, Nikolaos. Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor (EHW). 12/16/2002.

- William Plate, LL.D. "JOANNES III VATATZES". In: A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. II: EARINUS-NYX. Ed. William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1880. pp. 578-579.

- Will Durant. THE AGE OF FAITH: A History of Medieval Civilization - Christian, Islamic, and Judaic - from Constantine to Dante: A.D. 325 - 1300. (The Story of Civilization Series). New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950.

- David Jacoby and Michael Angold. "Chapter 17: Byzantium after the Fourth Crusade". In: The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume V c.1198 – c.1300. Ed. David Abulafia. Cambridge Histories Online. Cambridge University Press, 2008. pp.525-568.

Wikipedia

Other Languages

- Great Synaxaristes: (Greek)

Ὁ Ἅγιος Ἰωάννης ὁ Βατατζὴς ὁ ἐλεήμονας βασιλιὰς. 4 Νοεμβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- (Greek)

Ιωάννα Κατσούλα. ΑΓΙΟΣ ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ Ο ΒΑΤΑΤΖΗΣ. Ο μαρμαρωμένος ελεήμων βασιλιάς και η βασιλεύουσα. ΣΤΥΛΟΣ ΟΡΘΟΔΟΞΙΑΣ. ΝΟΕΜΒΡΙΟΣ 2011.

- (Greek)

Λαμπρά θυρανοίξια του Ι.Ν. Αγίου Ιωάννη Βατάτζη στο Διδυμότειχο. AMEN.gr. Nov 5, 2010.

- (Greek)

"Ασματικη Ἀκολουθία και Παρακλητικος Κανων εις τον Βασιλέα Ἅγιον Ἰωάννη Βατάτζην τον Ελεημονα". Εκδοσεις ΟΡΘΟΔΟΞΟΣ ΚΥΨΕΛΗ.

- (Greek)

Ιωάννης Γ' Δούκας Βατάτζης. Βικιπαίδεια.

- (German)

A. Heisenberg. "Kaiser Johannes Batatzes der Barmherzige". Byzantinische Zeitschrift, XIV (1905), pp. 160, 162.

External Links

- JONH III VATATZES EMPEROR. Principe Vatatzes. 24 December 2011.

- How did the Empire of Nicaea emerge as the front-runner of the Byzantine Successor States and eventually become the restorer of Constantinople? Ancient Sites. Jan 13, 2005.

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Church History

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > Liturgics > Feasts

Categories > People > Rulers

Categories > People > Rulers > Roman Emperors

Categories > People > Saints

Categories > People > Saints > Byzantine Saints

Categories > People > Saints > Greek Saints

Categories > People > Saints > Saints by century > 13th-century saints